(LinkedIn post by Nathan Faleide 19th Sept 2024).

As the AgTech bubble runs out of hot air, what have we learnt?

Is communication, or more specifically asking industry what they actually want, the main reason for the poor translation of the billions of dollars spent on the BigData, Drones, AgTech booms into on farm adoption and broad scale industry change?

When asked to put together an AgTech thought leadership article for The Australian Farmer I was a “on the fence”, as I am definitely not the best person to over promote the Agtech “unicorn”, and the words “disrupt”, “agile” and “game-changer” do not readily inhabit my vocabulary (nor that of any farmer I know). Then inspiration came from a posted article on social media’s LinkedIn that provided a perfect narrative for this story.

Before I get into this moment of enlightenment, you may ask “who am I?” and “what would I know?”. In response, I have worked within agricultural research for 30 years including extended stints with both the New South Wales and Queensland Departments of Primary Industries and for the last ten years with the University of New England (UNE). I have an associate degree, a bachelor’s degree and a PhD all majoring in remote sensing and Geographical Information Systems (GIS) and am currently the Director of UNE’s Applied Agricultural Remote Sensing Centre (AARSC), where we work across 20 industries globally. I am also an oyster farmer based on Moreton Island (Mulgumpin), Queensland, and President of the Queensland Oyster Growers Association.

Back to the LinkedIn article. It showed the following animation and the heading: Ag thought of the week: Is low adoption of certain AgTech solutions due to anxiety and fear?

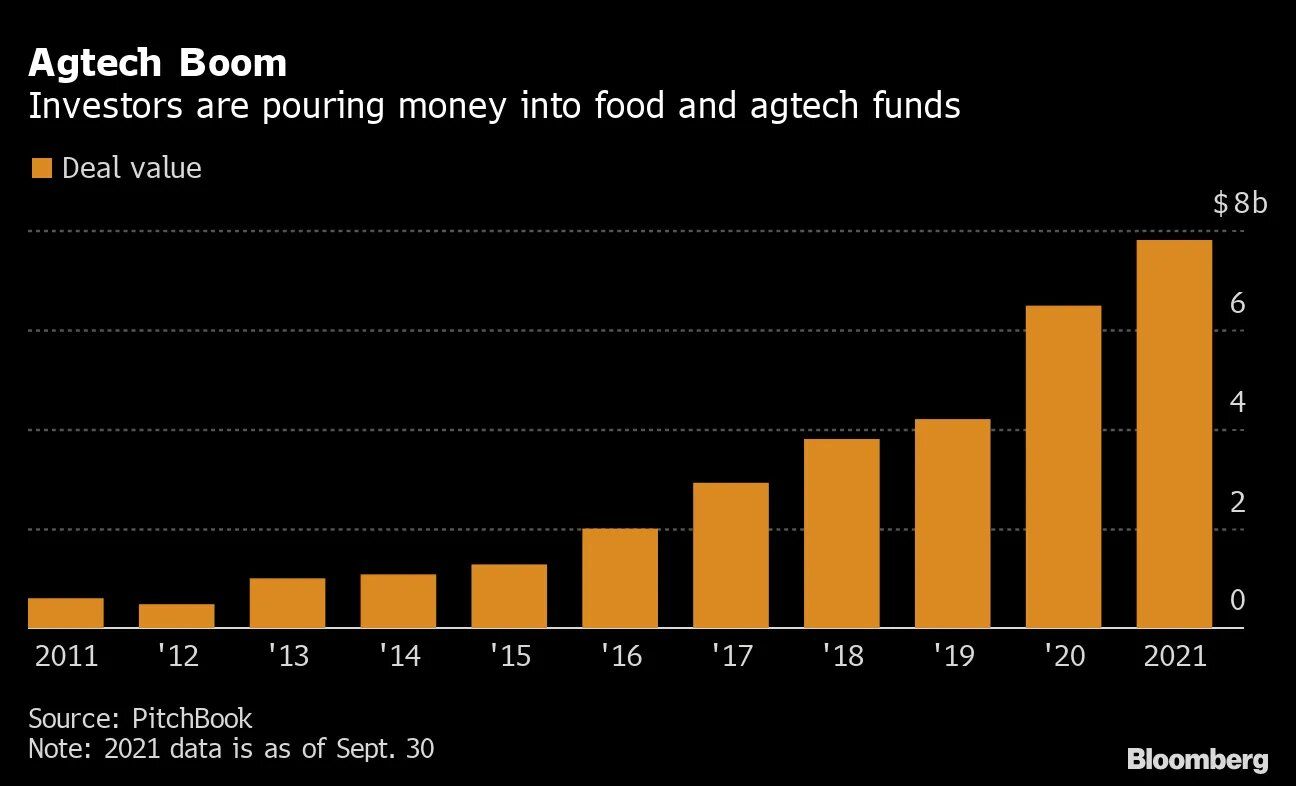

As mentioned, this stirred a reaction. Being around to see the Big Data, Drone, AgTech, Machine Learning /Artificial Intelligence and now RegenerativeAg booms, it astounds me (and surely fatigues all) that the same pattern occurs time and time again. A small whisper of these technological incarnations becomes a roar of frothing excitement where billions of dollars are spent on good salesmanship and invention which ultimately fails to translate to comparable advancement on the ground. The tech, the analytics, the accessibility are all there, so where does it go wrong? I simply believe this failure is predominantly due to a lack of communication between tech developers and industry need.

Going back to our bird scenario. The Agtech perspective on this is all about the cage that they have gloriously removed to allow the bird to be free (technological advancement). But as the bird doesn’t embrace this then it must be afraid or suffer from anxiety i.e. the bird’s fault. What if we started this process by asking or considering what the bird actually wants or why it is in a cage in the first place? Maybe it wants to be in the cage, maybe it doesn’t fly, maybe there is a cat sitting on the outside and by assuming the cage is not needed you have sentenced the poor fella to being lunch.

A simple way for Agtech providers to flip the scenario and put themselves in the “bird’s/ grower’s shoes” is do they own a robotic vacuum, an electric car, and a fully solar powered energy efficient building? If not why? They incorporate cutting edge tech, offer massive efficiencies (labour and power), and are better for the environment. Would it not be considered hypocritical if these developers do not have these latest technological advancements in their own places of business, are they scared? Furthermore, if they do in fact have all these things, have they read all the manuals to ensure they are using all the functionality appropriately to get the best result?

Following these trains of thought, I don’t think it’s fair to suggest a grower suffers from fear or anxiety because they haven’t adopted the latest tech. The failures are more likely to be due to the cost of tech, the relevance of the tech to their needs, the time required to learn and adopt it as well as change from current practice, and also ongoing support. There are many drones gathering dust due to difficulties in downloading, analysing and understanding the data, not to mention flat batteries and broken propellers.

From my experience, the following guidelines have led to the successful development and adoption of Agtech that transcends most of the “booms”. These are: find out what are the main three limitations to the current farming operation (the need); find out what are the current commercial practices and what are the short falls; find out what tech is best suited for the required application; find out how accurate and reliable is the proposed solution (validation); and then support on how to adopt, apply, interpret, and then maintain the technical solution into common day practice.

Tree crops: A nice example of application driving Agtech

Starting with the industry need. In 2014, CEOs from three Australian tree crop industry associations identified two main needs: The first was to have a more accurate understanding of the extent (location and area) of their respective industries, the second was having a more accurate way for predicting yield earlier in the growing season.

This request came at the start of the “Drone” and subsequent “Agtech” booms and as such there was the opportunity to throw everything at these two needs including satellites, drones, airplanes, robots, ML/AI, MobileApps, hyperspectral, multispectral, thermal, LiDAR, carrier pigeons. There was also the opportunity to bring together a strong collaboration of expertise from industry, university, government departments of primary industry and commercial developers. With all that engagement, testing and validation there were some wins that have been adopted and continue to grow.

The Australian Tree Crop Map Dashboard which identifies the location and area of all avocado, mango, macadamia, citrus, olive, and banana orchards nationally was developed using an integration of remote sensing (aerial and satellite), the digitisation of existing industry data, citizen science engagement through mobile and web based Apps and ground truthing. The mapping of tree crops was a major achievement for digitally empowering a number of industries by delivering essential base line data that provided an accurate measure of current industry size and annual change, informs decisions around labour, infrastructure, traceability, forward selling, and improved preparedness and response to natural disasters and biosecurity threats. The freely available map has been adopted directly on each industries website to assist grower engagement as well has been used by ABARES, the Australian Bureau of Statistics, Harvest trail, and the Murray Darling Basin Authority. This successful integration of Agtech and industry need has now encouraged many more industries to be mapped in Australia as well as other countries, it has achieved the glorious status of Agriculture 4.0.

For yield forecasting, I am still perplexed on how growers are supposed to navigate all the technologies, understand how to use them effectively “off the shelf” and how to integrate them into the farming system. No wonder the bird has anxiety.

In order to find the best solutions, the extended team assessed space, airborne, and ground based sensors including hyperspectral, multispectral, thermal, and LiDAR for accuracies and practicalities of use.

Here are some main findings and observations: From the very outset there was no information on how best to acquire drone imagery of tree crops for yield forecasting i.e. time of day, flight direction, image overlap, speed etc. Then it was found that no sensors could accurately count all the fruit on avocado and citrus trees due to fruit growing within the canopy, in short if you can’t see it then neither can optical sensors. Ground based sensors were able to count fruit on mango as the fruit hang below the canopy; historic imagery identifying seasonal growth patterns and their subsequent correlation to annual yield proved to be a reliable predictor for tree crop yield at the block and farm level (this methodology is now being deployed across seven countries); thermal imagery was the most accurate for identifying specific diseases such as Phytophthora; Specific wavelengths from hyperspectral imagery that were found to correlate with specific constraints were generally not transferable to other growing locations and seasons due to the influence of other growing constraints.

The moral of the story is that not one Agtech could do it all, and that it was the application that best dictated the best tech and analysis methodology to use.